British electoral politics in the 1980s were dominated by Margaret Thatcher, the prime minister for the whole of that decade. Similarly, Tony Blair dominated elections when he was in Downing Street from 1997 to 2007. In sharp contrast, the decade from 2015 to 2025 saw no fewer than six prime ministers come (and mostly go) – five Conservatives and Keir Starmer for Labour.

Traditionally, Labour has been reluctant to sack its leader, but if the May elections turn out to be as bad as the polls suggest, the party might well adopt the Conservative strategy of changing its leader as frequently as premier league football managers.

However, the data suggests that sacking Starmer after those elections would be a mistake. This is because voters focus much more on the performance of the government overall than the prime minister when it comes to casting a ballot.

If he were removed, it would also trigger a serious internal conflict in the party on the scale of the turmoil in the Conservative party over Brexit. This played a major role in explaining the Tories’ massive defeat in the 2024 general election.

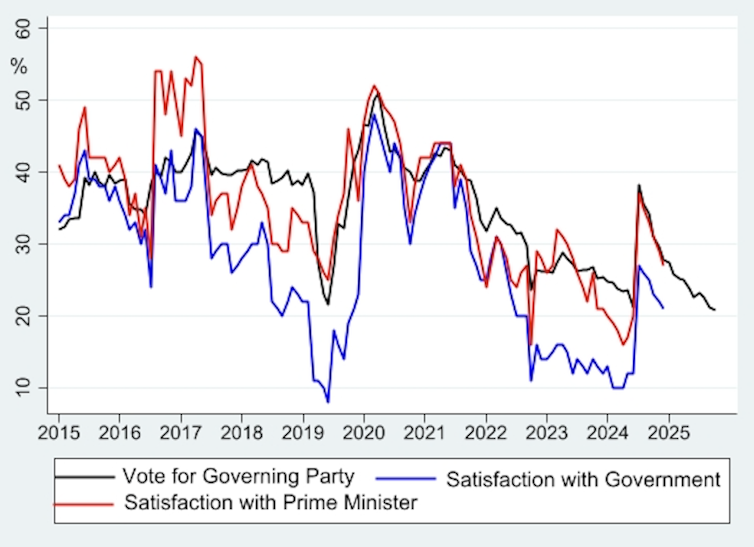

Trends in voting intentions, satisfaction with governments and with prime ministers for governing parties, 2015 to 2025:

To see why this is the case, we can examine polling data on perceptions of the performance of incumbent governments and prime ministers alongside data on voting intentions for their parties over the decade since 2015. The key comparison is between the effects of the performance of governments with that of prime ministers on the vote.

The relationship between these variables is very strong, with correlations all greater than 0.80. It is tricky to find out which of the satisfaction measures is most important for predicting the vote, but this can be done with the help of multiple regression. This is a statistical technique that can predict changes in vote intentions from the satisfaction measures together with some other variables which also influence voting for governing parties.

These other variables in the analysis relate to challenger parties affecting both Conservative and Labour governments. The three national challenger parties are Reform, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens.

In the case of Reform, I’ve included vote intentions for its ancestor parties, UKIP and the Brexit party, since it did not officially exist until 2021. The focus is on explaining voting intentions for the Conservative government from 2015 to 2024 and subsequently the Labour government up to 2025.

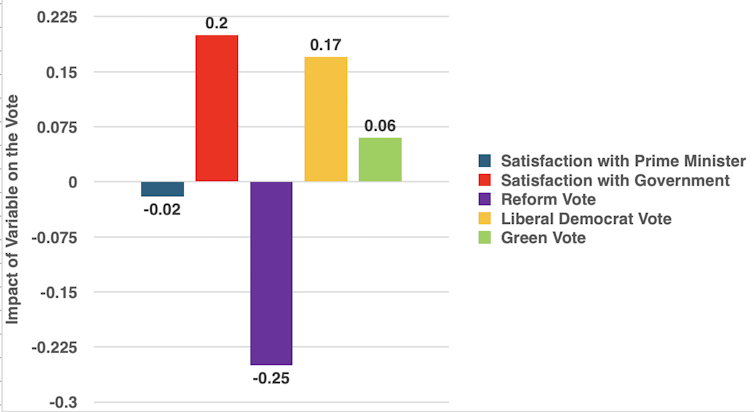

The effects of the satisfaction measures and the challenger parties on support for the governing parties appear in the chart below. The analysis identifies the impact of each variable on changes in vote intentions for the governing party.

To illustrate, a score of 1.0 would mean that a 1% increase in the satisfaction with government would produce a 1% increase in voting intentions for the governing party. In fact, the coefficient is 0.2, a lot less than 1.0 but nonetheless highly significant. An increase of 10% in government satisfaction increases government vote intentions by 2%.

Impact of variables on voting intentions for governing parties:

The same cannot be said about the effects of satisfaction with the prime minister. This had a negligible impact on voting for the government. It’s not surprising that polling on the popularity or unpopularity of the prime minister attracts a lot of media attention. After all, they are the main spokesperson for the party. But when it’s time to vote, this evidence shows people judge the government in general rather than the spokesperson.

A clear example of this is the fact that the rapid changes in the leadership of the Conservative party had little overall effect on the party’s support in the long run. They ended up losing terribly in 2024 despite the tendency to replace their leaders.

To be fair, there were exceptions to this, as can be seen in the first chart. After David Cameron resigned following the Brexit referendum his successor, Theresa May, was more popular than her party.

Satisfaction with her government rose, but satisfaction with her performance rose faster. However, she was subsequently brought down by her decision to break a promise and call an early election in 2017.

She nearly lost that election and as a result was unable to get a “soft” Brexit deal through Parliament and had to resign. Boris Johnson did win the 2019 general election, but his chaotic government prepared the ground for the electoral rout for the Conservatives in 2024

The challenger parties

Challenger parties all influence voting for the governing party. The strongest impact is seen in vote intentions for Reform and its ancestor parties. Reform took votes away from both Labour and the Conservatives when each was in government. An increase of 10% in the Reform vote reduces the support for the governing party by 2.5%.

The impact of the Liberal Democrats on the governing party has been negative when they are looked at without considering the complex interactions of voting in a five-party system in England and six-party systems in Scotland and Wales.

These complexities ensured that Liberal Democrat support increased with government support as some voters were drawn to Reform, or when Labour took over as the governing party. Finally, the impact of the Greens on government support was negligible.

These results suggest that a change of leadership in the Labour party will not have any significant effects on vote intentions for the party. The only way to improve things is for Labour to deliver on its manifesto promises, particularly on economic growth and so change the mood of the country.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.